To Make Something Better, We Have to Face It at Its Worst

You get the political space you take.

In 1994, Homocore Chicago marched into the Chicago Pride Parade without securing permits, permission, or anyone’s approval. They carried a massive banner reading: STONEWALL WAS A RIOT NOT A BRAND NAME, with a barcode painted across a large upside-down pink triangle. Budweiser had just started featuring drag queens in commercials, riding the wave of queer visibility while offering nothing meaningful in return. Homocore wasn’t fooled. They were calling out the co-optation of history—and the profiteering.

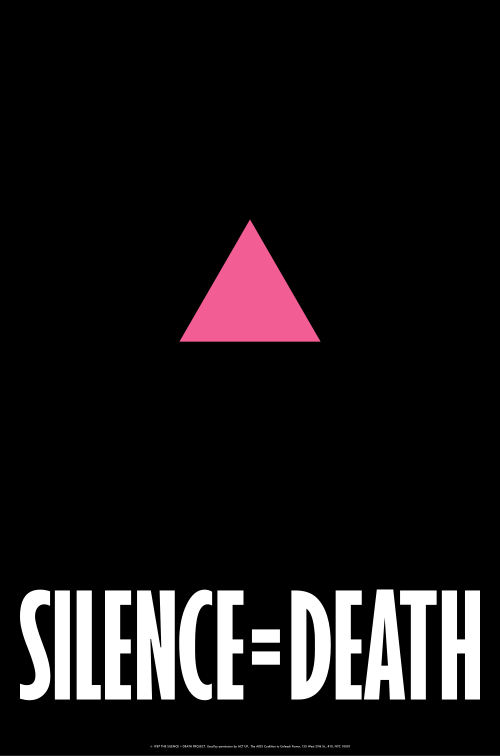

You know the pink triangle. You know Silence = Death because ACT UP made it impossible not to know. You know it because ACT UP insisted that the world recognize the AIDS crisis as a political catastrophe, not a natural one. You know it because ACT UP refused to be polite, invisible, or silent.

I was never a member of ACT UP though I was shoulder-to-shoulder with ACT UP Chicago members in many actions. I was close to Homocore Chicago where Joanna Brown and Mark Freitas created one of the most vibrant queer punk spaces the city ever saw—documented in Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution (2021), edited by Liam Warfield, Walter Crasshole, and Yony Leyser. Their work was inspired by G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce’s radical cultural invention in Toronto, where queercore emerged as a genre, a movement, and an identity: punk but queer, queer but angry, angry but imaginative.

Queercore traces the movement’s genealogy from early 20th-century German gay rights groups to Stonewall to the Gay Liberation Front and the Lavender Panthers. Queercore’s politics were never just aesthetic; they were an extension of liberation movements that refused domestication. They grew alongside—and often because of—ACT UP.

This brings us to Sarah Schulman’s monumental book Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (2021), built from 188 interviews across seventeen years. It is one of the most important movement histories ever written—dense, rigorous, mournful, and electric with political imagination. Alongside Jim Hubbard’s film United in Anger, which draws heavily on these interviews, Let the Record Show gives us a layered narrative of how desperate people invented new forms of organizing that changed the world.

Schulman writes that to make something better, we have to face it at its worst. That observation was about the AIDS crisis, but it rings painfully true today. The U.S. is confronting a new version of “the worst”—MAGA authoritarianism—layered atop old foundational horrors: Indigenous genocide, chattel slavery, the disenfranchisement of women, child labor, and racial capitalism. But for many middle-class white people, the rise of fascism is the first time they have felt genuine precarity.

ACT UP’s lessons are urgently relevant. What do people do when crisis becomes life or death? How do ordinary people generate courage? How do movements win when institutions fail? These two books push us to ask three questions that matter for every organizer, every teacher, every activist, and anyone trying to stop authoritarian consolidation:

Why are some people compelled to take political space while others wait to be organized?

How does disruptive, transgressive, nonviolent protest break open more political space?

How do people create joy, fury, art, and love during times of grief, fear, and death?

These questions guide this review—and point toward the strategic organizing pivots we need now.

Raise Your Hand for the Resistance & Revolution

Schulman describes herself as a rank-and-file ACT UP member who joined in 1987 after years of writing about AIDS. She stayed until 1992, when she helped found The Lesbian Avengers with five other women. Her book refuses a clean chronological arc. Instead, it is organized into four “books”: ACT UP’s origins; art as a strategy; treatment activism; and the desperate actions that marked the early 1990s—including storming the NIH, fighting for women with AIDS to be counted, and staging political funerals that made grief impossible to ignore.

ACT UP’s organizational strength came from its diversity. It was not, as many remember, mostly white gay men. It included women, lesbians, trans people, people of color, immigrants, poor and working-class people, former Black Panthers, veterans of Latin American anti-fascist movements, labor organizers, and leftist cadres. As Schulman writes, ACT UP was “molecular,” composed of dozens of affinity groups and committees that acted semi-autonomously but gathered each Monday night in a mass meeting that looked, as Garance Franke-Ruta put it, “like Athenian democracy.”

Schulman appears again in Queercore, offering a sharp analysis of why movements need a radical wing:

“If you don’t have a left, your center is the left…and they have no credibility…

The moment that we’re living in now, there is no left. So the center moves very far to the right.”

ACT UP made assimilationist politics look tame. Their confrontational actions—even storming St. Patrick’s Cathedral—shifted the Overton window. They set the cultural terms that later victories relied on.

Halfway through her book, Schulman steps back to ask: Why these people? Why did they choose a life-consuming fight?

After 188 interviews, she discovered that ACT UP members shared no common demographic trait. Instead, they shared a characterological one: they could not sit out a historic cataclysm. They were people who, for reasons internal or learned, refused to be bystanders in a moment of moral emergency.

The same can be said of Homocore Chicago. Brown and Freitas were not bystanders. Queercore’s early architects—many of whom had ACT UP or AIDS activism backgrounds—chose to create political cultures that matched the urgency of their time. ACT UP changed not only medicine and policy; it transformed queer culture. It recast People With AIDS from victims to fighters. It recast queers from “weak and wimpy” to fierce, strategic, and uncompromising.

Jody Bleyle captures queercore’s political role:

“They need the freaks on the edges doing the cultural work…That was us.”

Movements need people who question everything. Queer realization often sparks that. As Scott Treleaven explains:

“When you realize the world lied about who you are…you start to analyze all the other systems you’re involved in.”

This is how political radicalization begins.

Schulman underscores that ACT UP’s diversity mattered because it changed the organization from within. Women, people of color, poor people, and trans activists brought practices forged in other struggles—nonviolent direct action, facilitation methods, collective care—and fundamentally reshaped ACT UP’s culture.

And always beneath it was grief. Schulman writes:

“This is the story of a despised group of people, with no rights, facing a terminal disease…Abandoned by their families, government, and society, they joined together and forced our country to change.”

Breaking the “Be Nice” Rule

The lessons from ACT UP are not plug-and-play answers to MAGA authoritarianism. But they offer something deeper: a template for courage, confrontation, and refusing the limits of civility politics.

Schulman makes clear that elitist strategies rarely create deep change. ACT UP was an organization where people died in front of each other. That level of precarity forces clarity about what matters and what doesn’t. Arrest loses its terror when you are already dying.

Jamie Bauer brought feminist direct-action principles into ACT UP: You don’t need permission to exercise your rights. If the state wants to arrest you, that is their decision—not yours. Civil disobedience is for people who cannot wait for persuasion to work.

Bauer says:

“There’s a certain point where they don’t want to change, but you can force them to change…”

Today, we need more of this—not less. Elites will not save us. Foundations will not save us. Those closest to suffering will lead, as always. Nonviolent direct action is not symbolic; it changes the terrain. It forces confrontation.

Schulman describes ACT UP’s tactical model:

A small affinity group becomes the experts.

They propose a solution.

They take it to decision-makers.

When rejected, they teach the larger group.

They design a direct action to force the change.

This model is adaptable to any issue.

ACT UP may have had 20,000 arrests. Many members knew they were dying—arrest meant nothing to them. They used their bodies as leverage because they had no other leverage left.

Direct action creates intimacy. It forces the powerful to see those they ignore. It disrupts media distortion. It stops the political erasure of marginalized people by refusing the invisibility imposed by polite society.

ACT UP was larger than life: 500–800 people at weekly meetings, 7,000 at “Stop the Church.” Schulman writes that members committed every day to facing “disgusting, overwhelming, unbearable suffering” and still acted.

ACT UP used direct action because institutions had written many of them off. Women with AIDS, IV drug users, and poor queer people had no direct lines to power. They created their own.

Good actions create tension. Risk-averse institutions—nonprofits, philanthropies, political parties—fear tension. ACT UP embraced it. Those who condemned ACT UP later celebrated them. History rewards courage, not timidity.

A Most Splendid Community

Relationships across race, gender, class, and experience were ACT UP’s greatest strength and its most painful fault line. Schulman argues that ACT UP’s success came from its diversity—its “most splendid community” according to interviewee Jim Eigo.

But that diversity also fed internal conflict, culminating in the 1992 split between the Treatment Action Group (TAG) and the broader membership. TAG pursued insider work with pharmaceutical companies and government. The majority of ACT UP continued combining inside and outside strategies. Those who stayed waged the crucial campaign that finally included women in AIDS clinical trials.

Schulman is blunt about white male supremacy’s role—even among marginalized white men. She calls TAG’s refusal to embrace broader politics “one of the most powerful examples of the strength of white supremacy”—an ideology strong enough to make people act against their own survival.

The split was devastating. Activists were already losing friends daily. Losing each other was catastrophic. Jim Eigo explains that movements need both insiders and outsiders, but women, people of color, and openly gay people were nearly always pushed outside.

ACT UP’s queer organizing emerged from exclusion—from feminist spaces, from labor spaces, from racial-justice spaces. Exclusion forced invention. As Schulman writes:

“Winning on an unfair playing field means not playing by the rules.”

The Fight Is Never Over

ACT UP changed the world. Protease inhibitors became widely available in 1996, transforming HIV from a death sentence to a chronic condition for those with access to care. ACT UP forced the FDA to fast-track drug access. They changed the CDC’s definition of AIDS to include women. They helped legalize needle exchange, founded Housing Works, and shifted research priorities toward opportunistic infections.

But AIDS is not over. More than 700,000 people in the U.S. have died. In 2016, 1,790 people died of AIDS in New York City alone—1,471 of them Black or Latinx, more than half living in extreme poverty.

Transformational change is generational. We win reforms, defend them, and build from them. Many ACT UP veterans now fight authoritarianism with decades of discipline behind them.

Schulman emphasizes ACT UP’s work ethic: “intellectually rigorous, emotionally brutal, physically exhausting.”

Even in death, they resisted. ACT UP’s political funerals—ashes scattered on the White House lawn, an open casket carried to George H.W. Bush’s campaign office—made private grief a public demand.

Jon Greenberg’s eulogy for Mark Fisher captures ACT UP’s ethos:

“Acceptance of our mortality…makes it possible to live life fully…

to live in real freedom because we are not afraid of the consequences of our actions.”

Queercore ends with a manifesto:

Rip it up. Start again. Shake the world. It still needs shaking.

BOOKS REVIEWED:

Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.

Warfield, L., Crasshole, W., & Leyser, Y. (Eds.). Queercore: How to punk a revolution: An oral history. PM Press, 2021

First published in Social Policy: Organizing for Economic and Social Justice (55)4.